Entropy

Inspired by this video on compression, I wanted to understand what carrying information actually means, from a few interesting examples relating to repeated random events (like how much information is required to encode flipping a coin 100, 1000, or more times).

Intuition for Entropy

Shannon entropy is the expectation of the number of bits required to encode a particular symbol.

Imagine if you took a character out of a string like "aaaaaaaaaaaa...". Since you know that every character is an a, there is actually very little information encoded (no information, if the length of the string has already been given). Similarly if you had a 99.9% chance of an a, there is still very little information encoded.

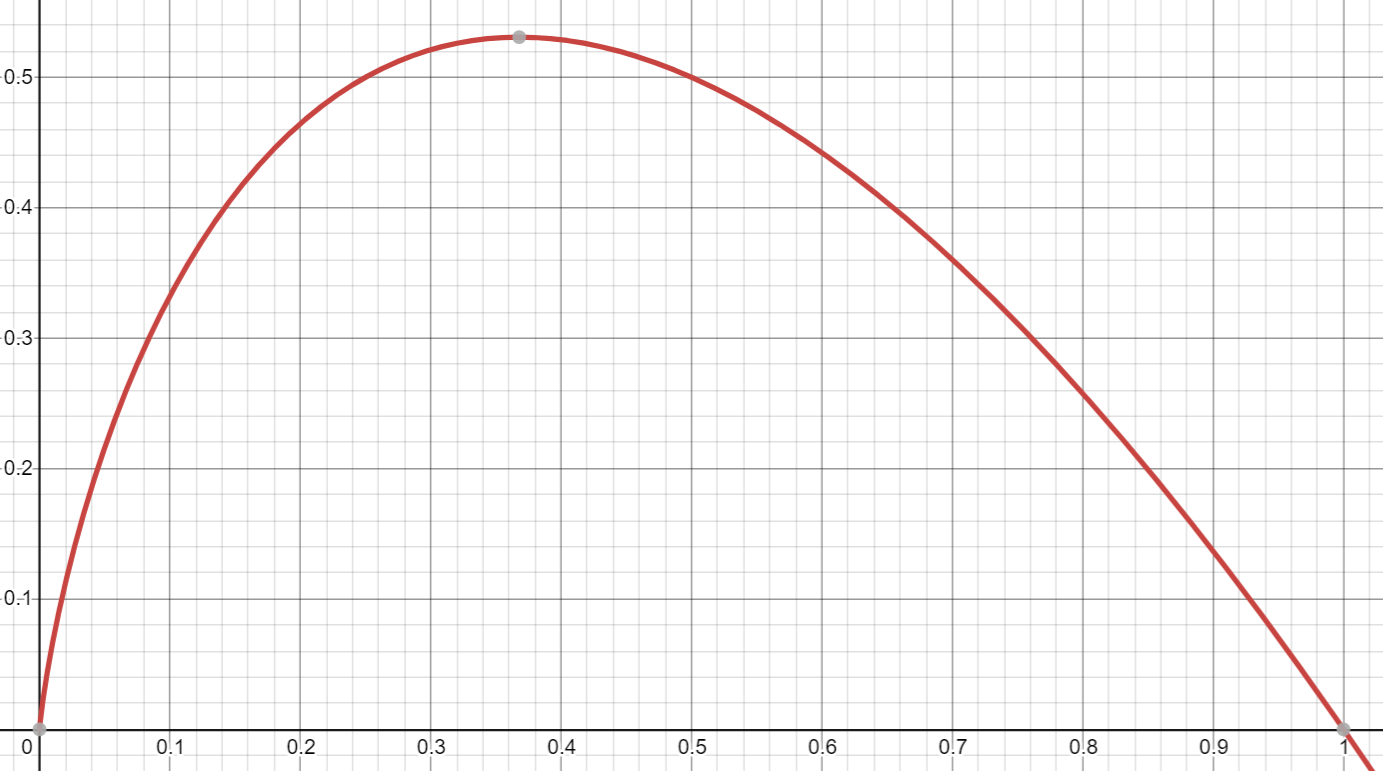

Therefore we can see that the entropy is inverse of the probability -- kind of. If the probability of an a gets really small, then you similarly dont need to encode it very often so its entropy becomes low. Really, we want a parabolic-looking function for the probability:

Here's a look at what the function inside the sigma looks like (using base 2). As the linear p term dominates, while in the middle, the logarithmic term plays a big role:

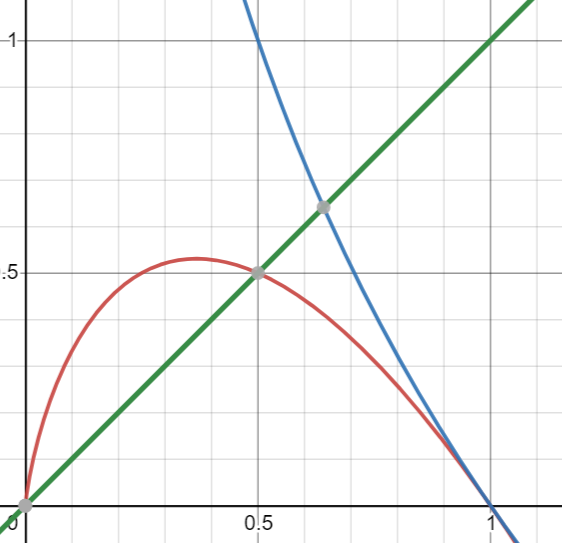

Here's maybe a more useful view. Red is function we are examining, green is a linear function and blue is a negative log:

One thing that might be confusing is how exactly the log of base 2 related to the number of bits of information. For a second imagine that we use base 10 instead of base 2. Now imagine the probability was .1, then .01, .001 etc. If we wanted to encode that these were the probabilities, then we would need to use digits. It's a similar thing for base 2, if we now consider numbers encoded in binary. Note that this isn't so much about the precision of the probability as it is about the magnitude; if we literally wanted to encode the exact probability and it were .100000000000000001 then we might need to use many more digits than the entropy predicts, even though it makes little difference.

Note that non-power of 2 probabilities, this explanation implies fractional binary digits, but we can accept this as the nature of such a metric.

Applying entropy

It's useful to think of where we can find entropy both in the natural sciences and in statistics.

The link to entropy in science

Entropy in physics, for example, is often stated as the number of microstates a system can achieve, ie all the ways the particles can be arranged etc. This is true, but there is also a probability component -- as probability diminishes to 0, the entropy a microstate contributes is small (it's so unlikely to occur). This mirrors the intuition for information theoretical entropy.

Entropy of the number of successes with the number of trials? (Binomial)

Let X be the binomial random variable that denotes the number of successes of n bernouli trials. The probability mass function is given by . We aim to find .

Here's a desmos with the function.

We see some interesting behavior. For a small number of trials, the entropy is small, but increases then rapidly drops to 0. The fact that the entropy rises for the first couple trials illustrates that entropy rises as more cases are possible (you can have a greater range of values in a binomial random variable of 2 trials than on 1 trial). The fact that it eventually limits to 0 shows us the value of repeated trials in increasing our certainty and thereby reducing entropy.